| Translated by Ekaterina Likhtik. |

My parents, Pavel (Faivel) and Eugenia (Sheindl-Yaffa) lived in Bendery, in Bessarabia. From 1918 to 1940 this region was controlled by Romania and their town was called Tigina. Despite the Judeophobic nature of the Romanian government, it didn’t preclude the legal growth of Jewish ethnic-religious life. There were five Jewish deputies in parliament, representing almost 800,000 of their brethren. The entire spectrum of Jewish political groups was present – from assimilationists and the orthodox to social Zionists and supporters of Zeev Zhabotinsky.

Periodically the authorities would introduce some form of anti-Semitic barriers. Naturally the Jews criticized and disapproved of the Romanian government in return, not realizing that all the actions of the Romanians were mere trifles in comparison to the upcoming Stalinist song and dance.

Both of my parents were the youngest children in their families. My mother had two older brothers and my father had three older brothers and two sisters. Beginning in the 1920’s, my parents’ brothers were active participants in the leftist Zionist youth movement “Hashomer Hatzair” (“The Young Guard”-Heb.). At that time the young dreamed of restructuring society according to Marxist principles. The idea was to leave behind everything old, traditional and diaspora-grown in order to create a new kind of Jew – a joyous and healthy kibbutz worker in shorts who would toil happily on his land.

The “ken” (“nest”-Heb.) of Bendery’s “Hashomer Hatzair” was regularly visited by instructors from Bucharest and from British-mandated Palestnian kibbutzim. Intense work was under way to prepare future immigrants for life after repatriation. Young men and women were taught professions that would be useful for adapting to “Eretz Israel” (the “land of Israel”-Heb.). My mother, Dolmatzky by birth, would go to the Romanian city of Galatz, where she worked on a farm to learn how to milk cows. In 1938-1939 my father would go to the Romanian town Bakeu where he worked at a factory owned by wealthy Jews that sympathized with Zionist ideas.

One after another, groups of “halutzim” left Romania – the first immigrants having gone through the ideological and physical training in “Hashomer Hatzair”. The Zionist leadership could always get them permission from the British authorities to enter, since these were not any immigrants (“olim”-Heb.) coming to Palestine, but rather a young corps of a Working Party ; strong, able and politically engaged builders of the best social order in the ancient land.

Sometimes the frontiers of idealistic battles would cut through family lines. For example Moishe Gorodetsky, my father’s brother, was a member of the right-wing Zionist organization “Beitar”. At the end of the 1930’s, the right-wing leader Zeev Zhabotinsky came to Bendery twice. When he was giving a speech at the Bendery civic hall called “The Auditorium”, young activists from “Hashomer Hatzair” forcibly entered the building and tried to disrupt the great orator’s speech with screams and chair throwing.

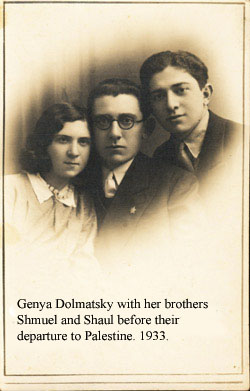

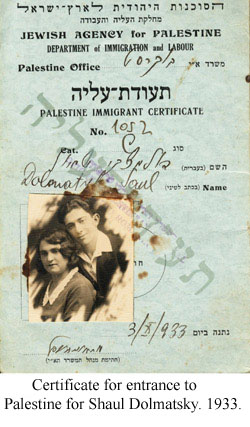

Two of my mother’s and two of my father’s brothers left for Palestine between 1932 and 1933. The plan was simple; let the older brothers get on their feet in the new place first, and then the rest of the family would make the journey. On July 1, 1936 my mother’s father, Ephraim Dolmatsky, wrote from Bendery to his sons Shmuel and Shaul in Palestine: “We know about the frightening days that you have to live through ever since the Arab disorder began. Every day the newspapers report the terrible events occurring where you are. And in every report, comes the death toll. We have to be made of steel, while the Arabs continue to be in control.”

After adoption of the “White Paper” of 1939, the British authorities limited quotas for entering Palestine to 75,000 over five year and demanded that illegal immigrants be subtracted from the final quota. According to the British plan, within five years, entrance to Palestine would only be possible with a permission from the Arabs.

Only 6 or7 of my father’s 15 member “Hashomer Hatzair” group of the Bendery branch, managed to leave between 1937-1939 as part of the illegal repatriation operation “Aliyah-Bet”. Among the “lucky ones” were Seika (Pinhas) Solomon, a future participant in the War of Independence, poet and activist in the Histadrut (Labor Union Organization-trans. note); as well as Gideon Faiman and Ruchale Mirinyansky.

My parents, who went through the entire pre-immigration training (“ahshara”-Heb.), didn’t manage to leave in time. In the summer of 1940 Stalinist USSR occupied Bessarabia and Buchovina while Hungary overran Transylvania – almost a third of Romanian territory, which contained an enormous Jewish population. Bendery, which suddenly became part of Soviet Moldova, was completely cut off from the outside world after the arrival of the Red Army. The iron curtain that fell in 1940 would only be broken through forty-eight years later.

My mother recalled the enthusiasm with which the Jews of Bendery welcomed their Soviet “brethren-liberators” – with flowers and open arms. The joy soon proved to be premature and the euphoria quickly diappeared. The Soviets immediately emptied out all the stores, sent the rich to Siberia and, in addition, between 1940 and 1941 the vengeful government agencies closed all the Jewish organizations of Moldova. Once branded a “Zionist” saving yourself became practically impossible. The Gorodetsky and Dolmatsky families were placed under NKVD (predecessor of KGB – trans. note) surveillance.

Hitler’s invasion in June of 1941 put a final end to any plans we still harbored to move to Palestine in the near future and to live with our relatives. My parents’ families managed to move first to Uzbekistan, where my parents got married in 1944, and then to the city of Kuibishev (present day Samara) on the Volga river.

The land of Israel became even more distant to them. In Kuibishev my brother Michael was born (1946) and then in five years I appeared (1951).

It’s important to note that my father asked to go to the front and to be on active duty but the Soviet leadership didn’t trust Romanian Jews. He was mobilized to the construction battalion that was building the Kamishin-Stalingrad-Saratov road.

However, even during the war the correspondence between the Gorodetsky family, now in Central Asia, and their family in mandate-controlled Palestine continued. Here are a few lines from Ephraim Dolmatsky’s letter to his sons in Haifa (April 12, 1943): “My dear children! We are alive and have our health, we are working, awaiting the destruction of the German marauders - and we will see it. We received the letter where you mourn for your dear mother, and we answered it right away. I send my love to you all by my pen. Your father, who never forgets you for a minute.”

During the Holocaust, my father’s brother, the Beitarist Moishe Gorodetsky, and many other relatives from Bendery, were obliterated by the Germans and the Romanians. My mother’s mother, Bracha Dolmatsky, died during the evacuation when she was run over by a passing train (Shmuel’s daughter in Haifa was named in her memory when she was born 9 months after my grandmother’s death). Ephraim wrote in a letter to Haifa: “You tell of such joyous news, you’ve given birth to the “Name” of my dearest unforgettable, beloved wife and your beloved mother. I will only calm down when I will be able to hold “Her” in my arms. I would like to speed it up, for life these days isn’t very long lasting.”

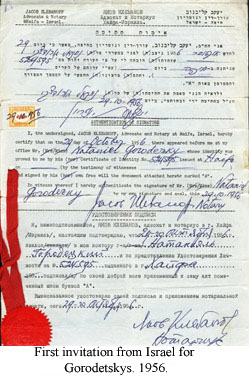

Attempts to leave while Stalin was in power could end tragically. Only during the more liberal era of Khruschev did we decide to apply for the exit documents as a whole family (grandfather, parents, my brother and I) and we even received an invitation from Israel. However, after some consideration we decided to play on the humaneness of the Soviet government and to apply only for my grandfather. We had thought that an elderly person would be allowed to be reunited with his sons after so many years apart. Once he left, we would also have more convincing reasons to demand an exit visa. In 1957 my grandfather, Ephraim Dolmatsky, applied to leave and to go to his sons Shmuel and Shaul in Israel. My 14-year old cousin Bracha Dolmatsky rejoiced at the upcoming reunion in her letter of Jan. 10, 1957 to my grandfather Ephraim: “I was very happy to hear that we will meet soon. I impatiently await your arrival. I want all those who remained alive to be with us as well. I am already thinking about how I will talk with you. I want to study Russian and Yiddish. I will see you soon!”

But the government showed heightened vigilance and uncovered our “insidious” plot. There wasn’t any meeting between granddaughter and grandfather; in that same year our family got our first refusal. Thus began the 32 year history of our fight with the Soviet system. Even then, in the 1950’s, our family felt the unspoken control emanating from informers and their superiors in the KGB.

My grandfather wrote to the highest Soviet authorities at the time, Anastas Mikoyan, Klement Voroshilov and the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, describing his wish to reunite with his sons whom he hadn’t seen in 24 years. The answer was simple: “Let them come to you.”

In 1964 when I was 13 years old, my family once again prepared an application to leave. The documents were sent in the summer, so as not to interrupt school. In the sixth grade at the time, I told my classmate, the honor’s student Irina Ulanova: “Next year, I’m not coming to school. We’re going to move to Israel.” “What’s Israel?”-she asked. “It’s a country, all my relatives live there”- I answered.

The preparation of all the documents was in itself no easy task, requiring references from work, from regional authorities and the residential committee. A stamp had to appear on each piece of paper indicating: “For exit to Israel for permanent residency”. Once again the family received a refusal of a permit to leave the boundaries of the USSR. My mother wrote a letter to the astronaut Valentina Tereshkova, but she didn’t help.

In the mean time my parents’ brothers in Israel became activists in the MAPAI party (predecessor of the present day Avoda- trans. note). Meir Gorodetsky was involved in developing industry in Netanya and was one of the founders of this city. Nathan Gorodetsky worked as a carpenter in Haifa. Shmuel and Shaul Dolmatsky were well-known activists in the regional Labor Union Organization of Haifa (“Histadrut”- Heb.).

The new generation of our Israeli relatives changed their Bendery last names to Hebrew ones: Meir Gorodetsky’s (meaning “of the city” in Russian – trans. note) children took the last name “Keret” (“little city” in Heb.) whereas Nathan’s children took the last name “Gidron” (using the three first letters of the old name).

In the middle of the 1960’s our relatives in Israel sent us word in a letter that, on a certain day, the radio station “Kol Israel” (“Voice of Israel” – Heb.) would play a birthday greeting in Yiddish to grandfather Ephraim from his children in Israel. On that memorable day we all huddled around the radio and were eagerly listening to the announcer’s every word. We even prepared a tape player to record the broadcast. And then we heard: “Our father and grandfather Ephraim is congratulated by his children and his granddaughter and wish him health, many years of life and to live to see the day when he can reunite with them.” Following this there sounded a tragic song from the times of the Holocaust called “The Shtetl is on Fire”. In the middle of the song it began to be drowned out by the Soviet scramblers.

Despite the obstacles put in their relatives’ way by the Soviet authorities, the brothers always retained a strong interest in Soviet successes and in the rare visits of Soviet performers to Israel. In November of 1957 our Israeli brothers wrote us: “We congratulate everyone with Sputnik. Let peace prevail! Then we will also have a small piece of this big world.”

Here are a few lines from a letter written by Shmuel Dolmatsky on the 16th of March, 1966: “The violinist David Oistrakh is playing here. Everyone impatiently awaited his arrival. All the tickets for his concerts were sold out in a few days. However, despite the fact that the tickets are expensive, we are going to one of the concerts.” And about the arrival of the troupe “Birch Tree” to Israel: “Birch Tree’s” appearance here – is hard to express in words. The auditoriums were always full. Such ballet and such folk dancing is simply a rarity.”

The family members wanted to see each other, to overcome the long separation. From the same 1966 letter: “Eugenia, you write that papa very much wants to see us in this life. Believe us dear sister, this thought doesn’t give us any peace. One time a secretary from the Soviet embassy advised us to wait patiently, after a negative reply to our request. I said to him: “Along with patience, you need years and my father is 81.” Now my dear ones, we’ll have to start our efforts once again.”

The Israelis – my parent’s brothers, understood that for the moment the “curtain” couldn’t be broken through and decided to come and visit us in the USSR. But a new obstacle appeared: Kuibishev was a closed city, crammed with military industry and foreigners weren’t allowed to visit.

Our Israeli brothers were obligated to follow a standard route of “Soviet tourism”, visiting only certain predetermined cities and living only in hotels. Thus we had to take a few unusual steps: in 1966 we came to Kishinev where my father’s brother Meir and my mother’s brother Shmuel also arrived.

It’s not easy to describe this meeting when my blind grandfather Ephraim touched the face of his son Shmuel after a 33 year separation. Grandfather stroked him and asked: “My son, why did you wait so many years? Now that I’ve gone blind I can't see you”

I remember my uncle Shmuel asking me about evidence of anti-Semitism. This is when I was still in school and I told him about something that happened to me in the classroom. In front of the entire class, one teacher, Seraphima Ivanovna, chided me for bad behavior by saying: “Gorodetsky – he is not Russian, he doesn’t understand; but you, you are Russians, you should understand the Russian language!”

From Kishinev, the brothers continued to Kiev, Leningrad and Moscow and my parents accompanied them throughout the trip. The brothers visited Joseph Tekoa, the Israeli ambassador to Moscow, who would later become the Israeli ambassador to the UN. He gave them some Zionist literature for dissemination in Kuibishev. The Jews of the Volga were given the magazine “Ariel”, the brochure “Israel in numbers” and other printed material. My father began spreading these booklets amongst the local Jews, trying to persuade them to send their application for emigration to Israel.

At that time a typical incident occurred: two books weren’t returned to my father and soon the same two books were presented to him at the local KGB office. It became clear that the two acquaintances, Zinovii Vernik and Efim Simson, to whom he lent the books had informed on him.

It’s not surprising that after this, Faivel Gorodetsky was often summoned to the local KGB office. He writes in his memoirs: “This is when our ordeal began. I was interrogated: who are my friends, with whom do I meet, with whom do I correspond?. Many times they held me at the KGB from morning until late at night.” At the city’s factories the KGB officials would assemble “general workers' meetings” where they branded Gorodetsky as a Zionist agent. Many acquaintances severed all contacts with Faivel.

Upon returning to Israel, the brothers remained with the painful impressions left by their meeting with their Soviet family. Everyone felt the weight of uncertainty and the obscurity of future possibilities for reuniting. Bracha Dolmatsky wrote us: “My father returned in a state of shock and depression – you can imagine. When he would tell us about the meeting and the departure, we would live through it with him all over again”.

Literary treatment by Shimon Briman

| Part 2==> |