An unusual demonstration took place recently in Moscow, highlighting one of the least attractive features of current Soviet policy towards those who wish to leave. Leading the demonstrations was Alexander Kholmiansky, who not so long ago completed a year and a half in labour camp. Now, together with his parents and his wife, he has taken, courageously, to the streets.

Alexander's problem is that his wife's father refuses to sign a document releasing those (family members) who wish to leave from future financial obligations to him.

This is not the first time in recent months that the somewhat bizarre "future" obligation has been used by Soviet authorities to refuse an exit visa. Ironically, in the case of Alexander Kholmiansky, this restriction means that he cannot now join his brother Michael, not so long ago one of the leading Hebrew teachers in Moscow, who now lives in Jerusalem.

During the demonstration, it was Alexander's father who was actually taken off to the police station and fined for "hooliganism." Naturally enough, the small banners which the family had prepared were seized almost as quickly as they had raised them.

Amid the global excitement of the new Soviet-American agreement on nuclear weapons and the imminent summit, it is easy enough to overlook the human dimension which, in the case of Alexander Kholmiansky, his wife and his parents, now keeps them from that part of their family which, after more than 10 years of struggling, has at last "come home."

The scene at Ben-Gurion Airport when the first half of the Kholmiansky family reached Israel was one of joy tempered with anxiety. Michael's wife Ilana has been one of the leaders of the recently created group, "Women Against Refusal," whose weekly meetings did much in the early months of this year to alert the West to the continuing injustices of divided families and hardship cases. Her departure was as welcome as it was unexpected. But with it, the Kholmianskys became a divided family; their battle for reunification has already begun.

In Jerusalem, Michael allows no day to pass without trying to help his brother. In Moscow, his brother seeks new ways of protest and publicity.

It is in Washington, however, that the fate of the Kholmiansky family may well be decided. Less than six months ago, when Secretary of State Shultz was in Moscow, he was handed a list of so-called "resolved" human rights cases. Alexander Kholmiansky's name was on that list. That is to say, the Secretary of State was told that no further obstacle lay in the way of Alexander's departure.

The Soviet Union is busy just now giving assurances of a global kind, upon which both the security and prosperity of many lands depends. Cannot a small, earlier assurance, be honoured? That is the question which the many friends of the Kholmianskys are asking; friends who include members of the Israeli Knesset, members of the British Parliament, and members of the United States Senate and Congress, many of whom have met Alexander in Moscow.

Alexander Kholmiansky is now 37 years old. It is 10 years now since, following in his brother's footsteps, he began to teach Hebrew to a small circle of Jews in the Soviet capital. Often warned to stop his teaching, in 1984 he was arrested and sent to labour camp. At his trial, he told the court: "Despite the punishment this court will give me, I will overcome it like all persecuted Jews have overcome their fate over thousands of years of their history."

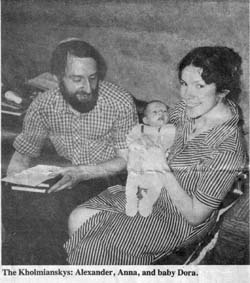

While Alexander Kholmiansky was in prison, many western politicians took up his case. After his release, it was assumed that the whole family would be allowed to leave. Alexander, back in Moscow, got married; he and his wife Anna now have a baby daughter, Dora, born this May.

It is Anna's father whose objections are now used as a barrier to the granting of exit visas, and the reunification of a small but remarkable family, whose contribution to the maintenance of Jewish life and spirit in circumstances so adverse, is surely a proud part of a history which must still be guided by human effort.

What better effort could there be, than to resolve once and for all this case which the Soviet authorities have already declared "resolved."

Published in �The Jerusalem Post� of October 7, 1987.